It’s the sound of “the jungles in the dead of night.” It “lures white women” into sex and sin. It’s the sound of “civilization” dying—and a new country becoming.

It’s 1920. The first war’s just ended. Black jazz musicians are migrating from New Orleans to major northern cities such as Chicago and New York. Nearly overnight, Prohibition’s given rise to the speakeasy, where the “devil’s music” accompanies drinking and dancing, and people from different genders, races, and social classes mix freely.

“Jazz is the accompaniment of the voodoo dance, stimulating half-crazed barbarians to the vilest of deeds,” proclaims Ann Shaw Faulkner, president of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, a powerful alliance of women’s social and reform groups that launches a crusade against jazz in 1921.

To its critics, jazz both embodies and amplifies the chaos of modern life. The music’s a menace not only to morals, but to public health. When people dance the Charleston, it’s said to resemble an epileptic fit.

Now, under all the talk of public welfare, there’s a steady stream of anxiety about both feminism and miscegenation. The critics are not subtle; they don’t have to be.

Thomas Edison, inventor of the phonograph, ridicules jazz, saying it sounds better played backwards. A Cincinnati home for expectant mothers wins an injunction to prevent construction of a neighboring theater where jazz will be played, convincing a court that the music is dangerous to fetuses. By the end of the 1920s, at least 60 communities in America enact laws prohibiting jazz in public dance halls.

But Jazz survives. No, it thrives. Soon you don’t have to leave home to get your “fix.” Radio and records bring it right to you. And while White moralists seek to suppress Jazz and persecute Black performers, White performers are helping themselves to the form (and laughing all the way to the bank).

Meanwhile, women aren’t only dancing to the new music. They’re making it. Specifically, African American women are making it.

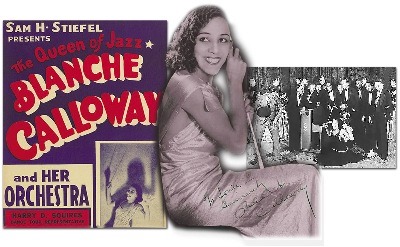

Before the decade’s out, Valaida Snow, a “hot trumpet player” in the Louis Armstrong mode, will earn the titles “Queen of the Trumpet” and “Little Louis,” performing everywhere from the Deep South to Shanghai. In the Midwest, Blanche Calloway will waive her baton before a twelve-piece, all-male orchestra. Singer, pianist, songwriter, bandleader and impresario Lil Hardin Armstrong will create some of the first all-female jazz bands in Harlem and Chicago. Ethel Waters, the superstar of Black theatrical revues, will be well on her way to becoming the highest paid Black woman in show business and the first African American performer to break the color line on Broadway.

Brave, smart, and sassy, these are some of the women who put the “Jazz” in the “Jazz Age.” There are too many of them, and their stories are all too fascinating, to fit into one lesson. But not to worry! More to come in future sessions of Flapper School, a new series about women in the 1920s.

In the meantime, if you’re looking to learn more about the utterly engrossing history of women in jazz, I recommend:

The Devil’s Music (BBC documentary)

Jazz (Ken Burns documentary)

add a comment

+ COMMENTS