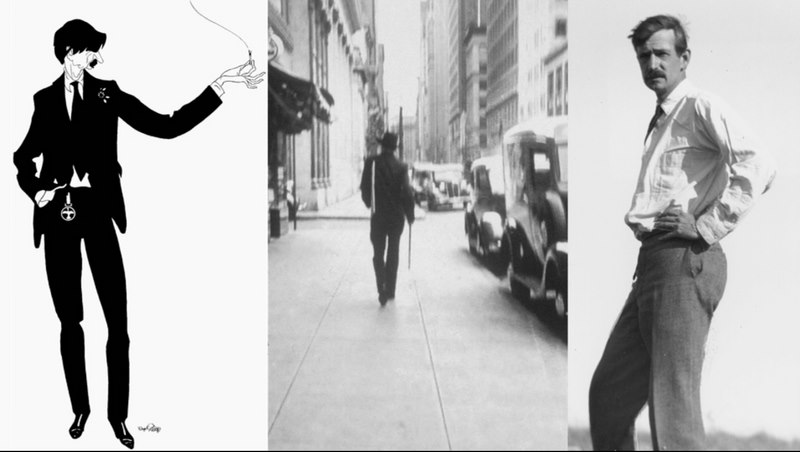

When he was a San Franciscan, Maynard Dixon strode through the streets each morning in a tailored black suit, black Stetson hat, and black cape. He was tall and very slender, with a long face, blue eyes, and blue-black hair. “Walks like a deer,” someone once observed, which would have been true if deer went around in hand-tooled, high-heeled cowboy boots.

Sometimes he sang a Navajo chant or Mexican folk song as he walked. Sometimes he just cursed the fog—loudly. Under his left arm he’d carry a canvas, and with his right hand he’d clutch the silver-tipped cane that bore the same image of a Thunderbird that served as his signature.

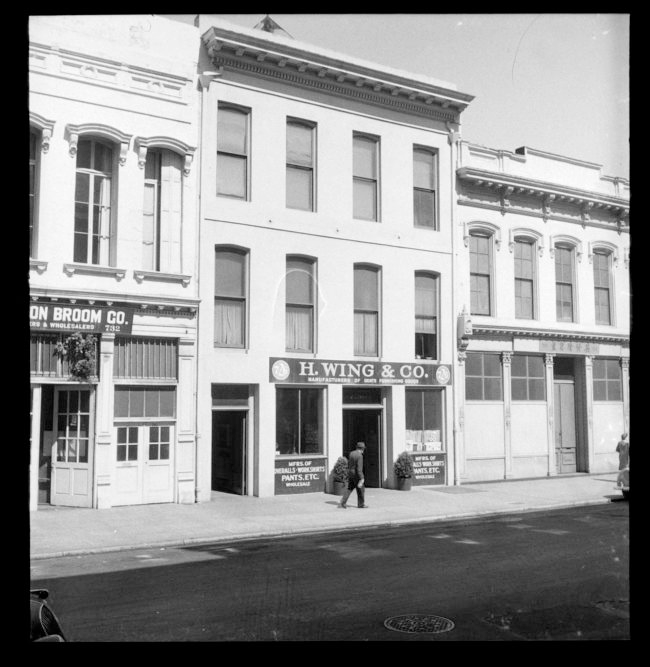

At 728 Montgomery Street he came to a tall green door. The building, like the nearby four-story Monkey Block, had survived the 1906 earthquake only to fall into grave, if picturesque, disrepair. To enter, he didn’t draw a key from his pocket; the door was never locked, night or day. Crumbling plaster, dark, dank stairways, ancient plumbing—you probably had to be an artist to love a place like that, which he was, so he did.

Oakland Museum of California.

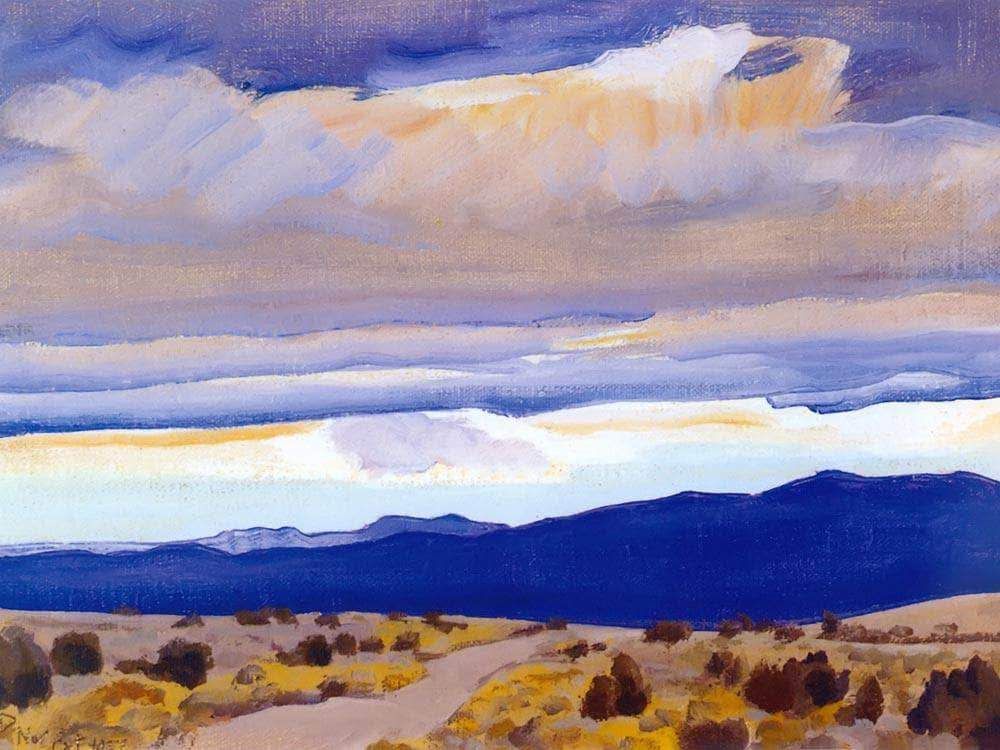

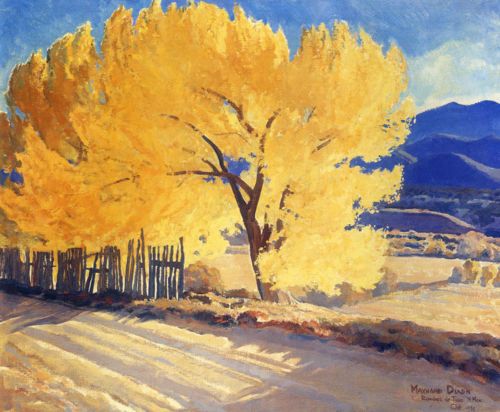

Inside, on the third-floor, he’d built a kind of temple. He filled it with Native American textiles, baskets, pottery, saddles, lariats, bridles. Here and there the walls were hung with his own paintings, which were luminous, colorful, breathtaking.

Wherever he went—in the City and surrounding areas, but also on long trips to Arizona and New Mexico—he carried little drawing pads in the pockets of his roomy jackets. As he roamed the West’s plains, mesas and deserts by foot, horseback and buckboard, he’d make hundreds of small, precise, painstakingly annotated drawings and sketches.

When he returned to San Francisco, he’d transform these into paintings.

“Nature is your starting point. You have eyes to see, nerves to feel, a mind to understand. Have respect for nature and your natural responses. Study the things that interest you, that awaken your imagination and nature will keep you sound.”

Maynard Dixon

For years he shuttled between San Francisco and the Southwest. Eventually the Bohemian bon vivant in him surrendered to the cowboy-wanderer-seeker. He left the City for good in the mid-1930s, but until then he went on working from field sketches, memory, and love.

Note for the curious: If you want to learn more about Dixon, there is a good 2009 documentary about him called Maynard Dixon: Art and Spirit. The best books about his life and work are by Donald Hagerty. Also, there are various murals and art works by him in San Francisco, including some stupendous murals in the Mark Hopkins Hotel.

add a comment

+ COMMENTS