Hiding in plain sight all over Northern California, the Bruton sisters must be one of the art world’s best-kept secrets of the last century. Theirs is the story of three brilliant, prodigious artists who created art of exceptional beauty and enduring resonance; the story of three women who dared to trespass the boundaries of social propriety to pursue their passions; three women whose lives offer powerful lessons about why women have been left out of history and what it takes for them to reclaim their rightful places.

The sisters enjoyed all the privileges of their class, but with one notable difference: their mother believed completely in her daughters’ artistic development and afforded them a then-rare freedom to pursue lives as professional artists.

As you know, much of my writing stems from a desire to shine a light of women whose stories have been lost, forgotten, or untold. But here’s the thing: I couldn’t write the books I write without the work of historians, journalists, and other writers of non-fiction, most of them women, who comb the archives and hunt down the sources necessary to assemble a truer, richer record of the past.

When I was writing The Bohemians, Linda Gordon’s Dorothea Lange: A Life Beyond Limits was an invaluable resource. It helped me lay down the tracks on which my imagination could journey.

Wendy Van Wyck Good’s new book Sisters in Art: The Biography of Margaret, Esther, and Helen Bruton is a similarly illuminating and heroic work. It exposed me to three remarkable women artists who were part of the Bohemian renaissance in early twentieth-century San Francisco. Women who brushed shoulders with many of “my” Bohemians: Imogen Cunningham, Maynard Dixon, Ansel Adams, and Frida Kahlo. (One of the sisters even lived in Monkey Block!).

In the months since The Bohemians came out, I’ve often been asked if I would have liked to live in San Francisco in the 1920s and 1930s. My answer has always been a hearty “Yes!” but learning about the Bruton sisters made that dream even more vivid and alluring.

During their lifetimes, Margaret, Esther, and Helen were known collectively as the “famous Bruton sisters.” Born to Irish immigrant parents who seemed to embody the “rags to riches” version of the American Dream, their childhood home in Alameda was one of the largest mansions in the Bay Area, an elegant testament to the family’s fortune.

The sisters enjoyed all the privileges of their class, but with one notable difference: their mother believed completely in her daughters’ artistic development and afforded them a then-rare freedom to pursue lives as professional artists.

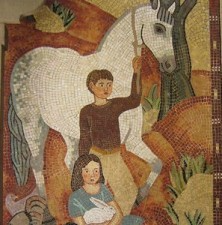

While their wealth afforded them opportunities out of reach for most women at the time, what they did with their opportunities was nothing less than revolutionary. Of the three, only one married, and only in her forties, and none of them had children. Each sister was gifted in her own way, and pursued her art with grit and verve—Margaret in painting; Esther in murals, fashion illustrations, and decorative screens; and Helen in large-scale mosaics. All three attained recognition during their lifetimes in the form of awards, commissions, and inclusion in prominent artistic societies.

Barns on Cass Street by Margaret Bruton

But how could three women of such accomplishment simply. . .disappear? The answer in part lies in the fickleness and vicissitudes of the art world. Abstract expression, the style that dominated the 1940s and the 1950s, was a male-dominated world and it showed no regard for the modernist style that characterized much of the Brutons’ art. During those decades the Bruton sisters’ emphasis on the American scene and the social realism of their WPA-era work also fell out of favor as a backlash against politically engaged art.

In Sisters in Art, Van Wyck Good, a Monterey-based librarian who has dedicated herself to uncovering and documenting the Brutons’ lives, writes of how the sisters’ aversion to fame and self-promotion likely contributed to their obscurity.

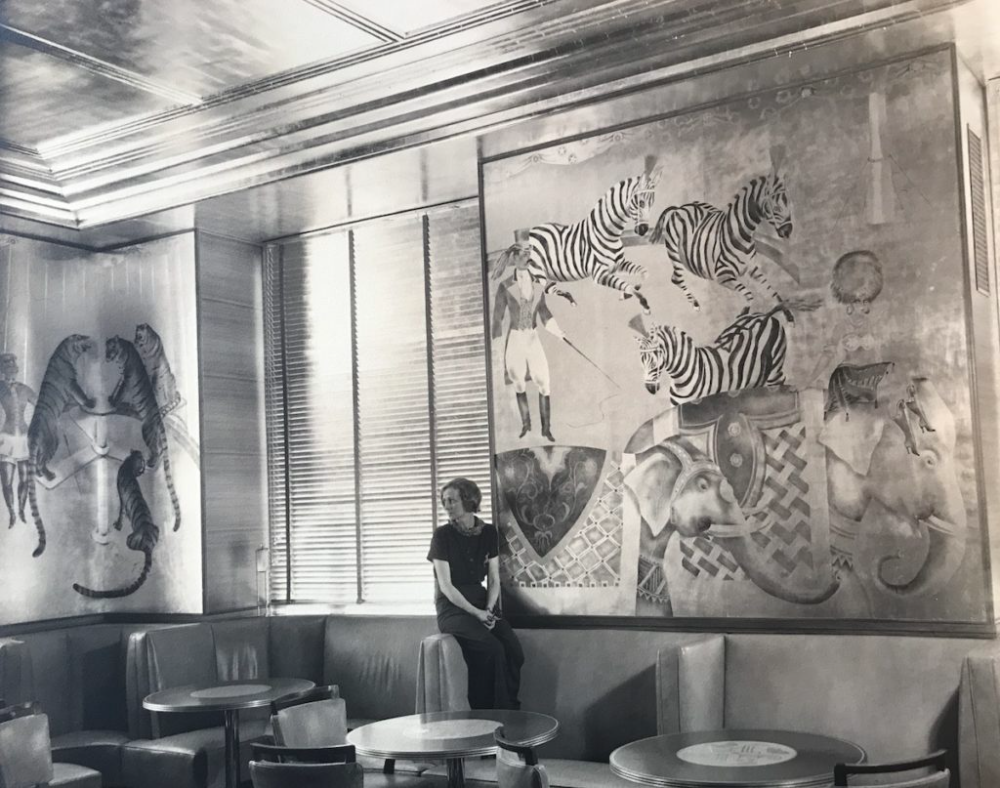

She also writes vividly about how all three Brutons continued to make art until the very end of their lives. Tragically, much of their work would be destroyed when the home of a collector went up in flames during the Oakland Hills fire of 1991. Some notable exceptions of their art survive in San Francisco: Esther’s murals in the Cirque Room at the Fairmont Hotel and Helen’s mosaics at the Hotel Union Square and at the San Francisco Zoo.

Though I haven’t yet had a chance to see them in person, I’m utterly captivated by photographs of the Cirque Room murals. They’re strikingly beautiful but also sweetly irreverent, which suggests so much about their creator’s personality.

I hope that if you’re in the Bay Area, or planning a visit here in the future, you’ll seek out Sisters in Art as well as the Brutons’ surviving art works. Van Wyck Good’s blog is a treasure-trove of stories and images about the sisters and features information about where and how to find their art. And if you do go in search of the fabulous Bruton sisters, drop me a line at jasmindarznik@gmail.com to tell me all about it!

add a comment

+ COMMENTS