Two Women, Separated by 43 Years, Bound by the Same Question: How Do You Make Art from the Life You Have?

Imogen Cunningham was sixty-seven years old when she met Ruth Asawa in San Francisco in 1950. In those days, she wore a thick wool skirts and sensible shoes and tucked her white hair under scarves. Everywhere she went in the city—and the woman went everywhere—she carried a camera slung across her chest.

People had taken to calling her the “grandmother of photography,” a title she detested, suggesting, as it did, a demure retirement that bore no resemblance to the life she was living.

She was teaching photography at the California School of Fine Arts alongside Dorothea Lange and Ansel Adams. San Francisco’s art schools were teeming with fresh talent, and word had spread about a young artist who’d recently arrived from Black Mountain College and was making uncanny sculptures from wire.

Asawa was twenty-four, Japanese American, daughter of lettuce farmers and an internment survivor. She’d studied under Josef Albers at Black Mountain and spent her summers on farms in Arkansas, harvesting onions by day and sketching by flashlight at night.

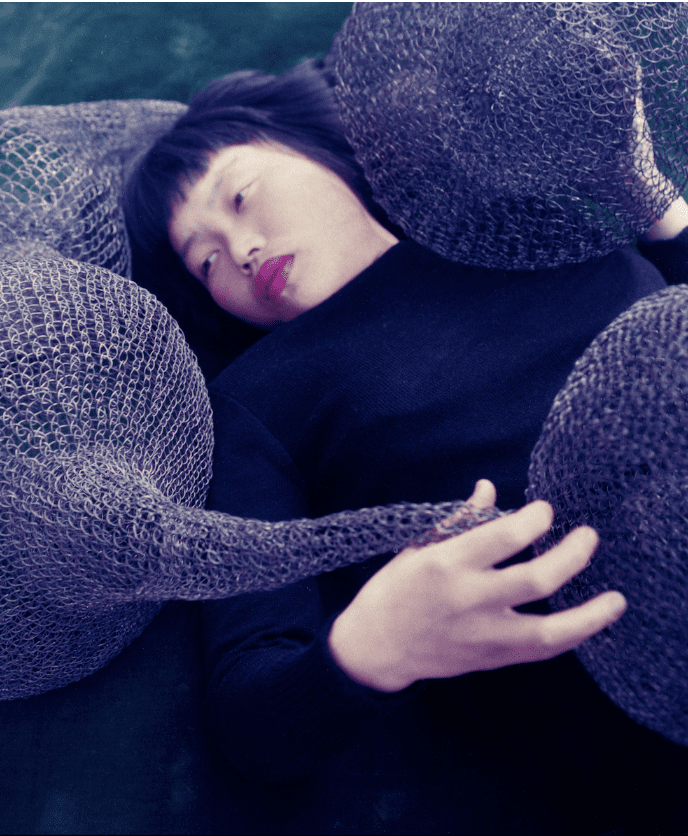

Asawa’s imagination had been trained on labor, repetition, and constraint. Her materials were humble—galvanized wire, pliers, steel—but her forms were both earthy and ethereal, suggesting fishing nets, the curves of the body, the shapes of memory. She moved through the world with an intense focus—grounded, deliberate, and deeply attuned to beauty in everyday life. While soft-spoken, she possessed an extraordinary clarity of vision, both in her art and in her convictions.

When she encountered Ruth Asawa in 1950, Cunningham had survived the modernist upheaval and emerged uncompromising and fully herself. She’d built a darkroom in a laundry closet and raised three sons while exhibiting her photographs internationally. Now edging toward her seventies, she was working as hard as ever, maybe harder, and her irreverence—sharp-tongued, unapologetic—was its own kind of art.

Despite their forty-three year age difference, the two became close friends. The young artist was building new forms from old materials, shaping a new language from silence, and Imogen was there to document it. Through her lens, she elevated Asawa’s work at a time when few others were paying attention.

For Cunningham, who had spent a lifetime pushing against the limits imposed on women artists, there must have been something exhilarating in Asawa’s defiance of categorization.

And for Asawa, Cunningham offered more than documentation; she offered a lineage she may not have expected to find, a lineage that showed a woman could live a long, unapologetically creative life. That motherhood and art weren’t enemies. That it was possible to keep making, keep seeing, all the way through.

Cunningham’s portraits of Ruth Asawa would become some of the most enduring photographs of Asawa’s career. They almost always show her in motion and mid-work, but also often making art in her Noe Valley home surrounded by her children.

What did they talk about, this salty grande dame of photography and her soft-spoken and brilliant young friend? If the pictures are proof, it had something to do about time—how to find it, how to protect it, how to make it mean something, even when no one was watching, especially when no one was watching.

In 1973, Imogen Cunningham photographed Asawa’s installation at the San Francisco Museum of Art. By then Asawa was a mother of six and beginning to be recognized outside the Bay Area. The sculptures hung from the ceiling, nested lobes of looped wire forming a wondrous constellation. Beneath them stood Imogen Cunningham, ninety years old, her camera raised to meet their beauty.

A Particular Kinship

I first saw Ruth Asawa through Imogen Cunningham’s lens—those silver prints where she’s caught in the heat of creation. I was writing The Bohemians then, immersed in the world of Dorothea Lange and 1920s San Francisco, tracing a lineage of women who had made lives from seeing. Lange’s friendship with Cunningham was a vital part of Lange’s coming of age. These were women who made beauty out of what they had—and passed it on.

A few weeks ago, I walked through the Ruth Asawa retrospective at SF MOMA. I stood before one of Cunningham’s portraits of Asawa and felt the presence of both women inside the frame.

The Bohemians are very much with me still. They return in moments like this—when one artist’s gaze opens the door to another, and the past expands in luminous, unexpected ways. This is the joy of research, yes, but more than that, it’s the particular kinship we can find through stories and art.

add a comment

+ COMMENTS