“Obsessed with Light” Resurrects a Forgotten Revolutionary

There are artists who disappear so completely from cultural memory that their rediscovery feels like archaeology—not just of their work, but of entire ways of seeing the world. Loïe Fuller was such an artist. Watching Sabine Krayenbühl and Zeva Oelbaum’s documentary Obsessed with Light, I found myself wondering how a woman who essentially invented modern dance, pioneered cinematic special effects, and transformed theatrical lighting could have vanished so thoroughly from our collective memory. But then, as I watched Fuller’s serpentine silks billow across the screen in hypnotic waves of color and shadow, I remembered: this is what happens to women who create entirely new forms of art. They get erased, their innovations attributed to the men who came after, their genius reduced to footnotes.

Obsessed with Light is an act of historical reframing—a film that insists on resurrecting not just Fuller’s story, but our understanding of who gets to be remembered as a revolutionary.

—

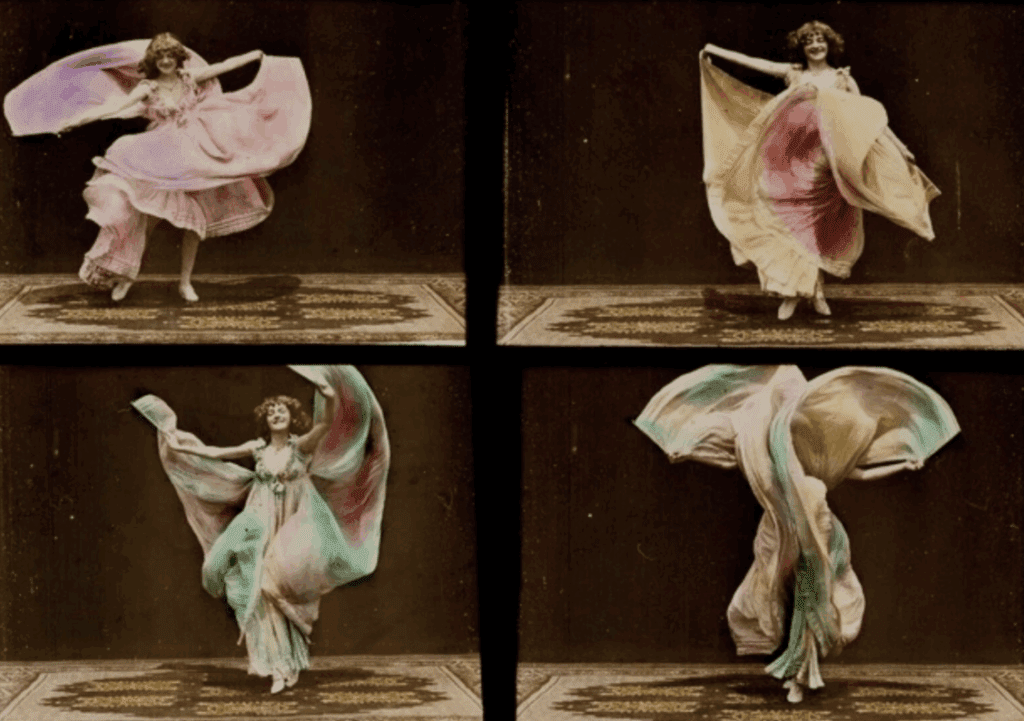

The Fuller that Krayenbühl and Oelbaum excavate is nothing like the vaudeville dancer most people imagine when they encounter her name at all. Here was a 30-year-old American woman who arrived in Paris in 1892 and, within months, had transformed herself into the most sought-after performer in Europe. The film opens with archival footage of her serpentine dance—Fuller draped in hundreds of yards of silk, manipulating the fabric with wooden wands to create shapes that seem to breathe and flow like living creatures. Under her revolutionary lighting design, she became fire, ocean, butterfly, storm.

But Fuller wasn’t just performing magic; she was inventing it. Obsessed with Light meticulously documents how this self-taught innovator developed the first theatrical underfloor lighting, created new chemical processes for colored gels, and designed mirror systems that multiplied her image into infinite kaleidoscopic patterns. She held multiple patents for her inventions. She filmed her own dances as early as 1905, experimenting with hand-painted film stock and double exposures that wouldn’t become standard cinema techniques for decades.

The documentary’s greatest achievement is showing us Fuller not a mysterious muse, but a brilliant inventor, savvy businesswoman, and tireless self-promoter who understood exactly what she was creating. Through a combination of rare archival materials, expert interviews, and stunning contemporary recreations of her dances, the filmmakers reveal an artist who was simultaneously ancient priestess and futurist prophet—someone who seemed to channel elemental forces while engineering the very technologies that made such channeling possible.

—

What makes Obsessed with Light more than just an artist biography is how it situates Fuller within the broader networks of creativity that sustained her. The film traces her relationships with other groundbreaking women: the sculptor Auguste Rodin, who became both mentor and collaborator; the photographer Samuel Joshua Beckett, who captured her performances in hauntingly beautiful images; her romantic partnership with Gabrielle Bloch, who managed her career for decades. Here was a woman building not just an artistic practice, but an entire alternative family structure that allowed her unprecedented creative freedom.

The documentary is particularly strong on Fuller’s influence on other artists. We see how her innovations directly inspired Isadora Duncan (though Duncan would later claim to have invented “free” dance), how the Lumière Brothers borrowed her lighting techniques, how Toulouse-Lautrec and other painters tried desperately to capture her effects on canvas. The film suggests—convincingly—that Fuller’s work was foundational to both modern dance and cinema, though her contributions to both have been systematically overlooked.

There’s a heartbreaking section about Fuller’s later years, when changing tastes and younger competitors pushed her from the spotlight. She died in 1928, relatively poor and largely forgotten. The film’s final third becomes a meditation on artistic legacy and cultural memory—who gets preserved, who gets erased, and why.

—

Visually, Obsessed with Light is itself an innovation. Krayenbühl and Oelbaum have created something that feels less like traditional documentary and more like visual poetry. They use contemporary dancers to recreate Fuller’s performances, but instead of trying to replicate her exact movements, they capture the essence of her work—the way light and fabric and motion combined to create something that transcended performance and became pure experience. The film’s lighting design pays homage to Fuller’s innovations while creating something entirely contemporary.

The archival materials are extraordinary. Rare film footage shows Fuller’s actual performances, though frustratingly brief and often damaged. More numerous are the photographs—haunting black-and-white images that capture her mid-transformation, silk cascading around her like frozen water. Perhaps most moving are the sketches and technical diagrams from her personal notebooks, evidence of a mind constantly inventing, always pushing toward new possibilities.

The contemporary interviews are thoughtfully chosen. Dance historians and feminist scholars provide crucial context, but the filmmakers wisely avoid talking-head syndrome. Instead, the experts’ voices layer over the visual material, creating a kind of scholarly chorus that illuminates rather than interrupts Fuller’s story.

—

What struck me most powerfully about Obsessed with Light is how contemporary Fuller’s struggles feel. Here was a woman fighting for artistic recognition in an industry dominated by male critics and impresarios, dealing with imitators who stole her techniques without credit, struggling to maintain financial independence while creating work that challenged conventional boundaries. Sound familiar?

The film doesn’t belabor these parallels—it doesn’t need to. The connections between Fuller’s era and our own emerge naturally from her story. Then, as now, innovative women faced the choice between commercial success and artistic integrity. Then, as now, women who created new forms of expression found their work dismissed as novelty rather than recognized as revolution.

But Obsessed with Light also shows us something hopeful: how artistic influence moves through generations like an underground river, surfacing in unexpected places. We see contemporary dancers who have rediscovered Fuller’s techniques, lighting designers who study her innovations, feminist scholars who recognize her as a foundational figure in performance art. Her work survived even when her name didn’t.

—

There are moments in Obsessed with Light when you can almost see the future being born. Fuller manipulating light like a sculptor shapes clay. Fuller experimenting with film techniques that wouldn’t become standard for decades. Fuller creating what might have been the world’s first multimedia performances, combining dance, visual art, technology, and theatrical spectacle into something entirely new.

This is what visionary art looks like: not just beautiful objects or memorable performances, but new ways of seeing, new possibilities for what art can be and do. Fuller didn’t just dance; she created an entirely new language of movement and light. She didn’t just perform; she invented the very technologies that made her performances possible.

Obsessed with Light succeeds because it treats Fuller with the seriousness she deserves—not as a curiosity or a footnote, but as a revolutionary who fundamentally changed how we think about the relationship between art and technology, between performer and audience, between individual creativity and collaborative innovation.

The documentary asks us to consider what other stories we’ve lost, what other revolutionaries have been erased from our cultural memory. It suggests that recovering these stories isn’t just about historical accuracy—it’s about understanding the full scope of human creativity and recognizing the patterns of erasure that continue to shape whose voices get heard and remembered.

In the end, Obsessed with Light does more than resurrect Loïe Fuller. It reminds us that the past is never really past, that innovative women have always existed, and that their stories—when we bother to seek them out—illuminate not just their own genius, but possibilities we’re still learning to see.

Fuller once said she wanted to create “the poetry of motion.” Watching this documentary, you understand she succeeded beyond her wildest dreams. The poetry lives on, waiting to be rediscovered by each new generation of seekers brave enough to dance in the spaces between art and technology, between memory and possibility, between what was and what could still be.

add a comment

+ COMMENTS