By force of time, but also immigration, my family’s lost many things. Some we’ve thrown away. But photographs, never. Ten years ago, when my mother began her descent into dementia, I became the custodian of the family photographs. I’ve boxed them up and taken them wherever I move, the way the ancients traveled with their ancestral masks.

This past year I’ve spent many hours sifting through these old photographs. Without my usual routines and habits, I’ve fallen out of focus. Amid so much uncertainty, I’ve found comfort returning to the past, and pictures offer the surest connection to it.

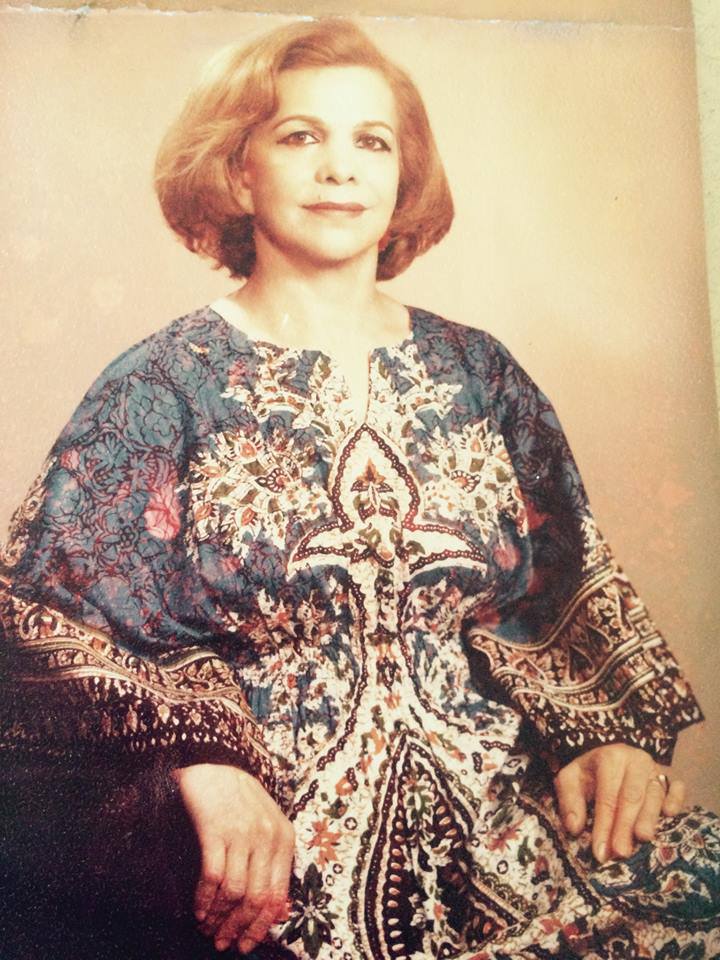

What I’ve craved is familiarity. Just as often what I’ve found has surprised me, but no picture has done so more than the portrait I discovered of my grandmother.

As a rite of passage and proof of prestige, the formal portrait belongs to a mostly vanished world. It’s an artifact from a time when having a picture taken was an occasion. An event. For generations a formal portrait wasn’t a mere document but an assertion of self-hood: I’m here. Remember me. The more wealthy and powerful you were, the more frequent, and lavish, the assertion.

I have no pictures of my grandmother as a young woman in Iran, no picture of her from the years she was a wife and then a divorce. It tells a kind story about her life then, and also how the world looked at a single woman of limited means, which is not at all.

By the time I came into her life, that woman was gone. In her forties my grandmother underwent an astonishing transformation. For years she’d been supporting herself by taking in sewing, but one day a new idea of herself rose in her head and insisted on making itself visible. She turned her apartment into a beauty salon, where she’d work for three decades, almost up to her death, achieving a degree of success that might seem modest now, but that wasn’t modest at all.

The portrait of my grandmother belongs to that time.

In my memories I see her in a simple cotton dress, her hair pulled back with a kerchief as she stands before the stove, frying eggplant as her rice crisps on the back burner. In the portrait she wears a splendid paisley print garment. I thought she wasn’t the sort of woman to have her portrait done or to wear such an item of clothing; the portrait tells me she was both.

What I see now when I look at this picture is the immense self-regard it took for her to walk into a portrait studio in 1960s Iran and ask to have her picture taken. It’s as simple, and timeless, as the desire to be seen, to be someone instead of nothing, to be known and remembered by those we love and leave behind.

That day the camera gave her a version of herself as she wished it to be—as she’d willed herself to be. In fashioning herself for a portrait, she was telegraphing a message no less urgent now than it was the day she walked into a portrait studio more than half a century ago: a woman who possesses herself is a beautiful woman.

Flush with the knowledge, she looked toward the camera, steadied her gaze, and smiled.

add a comment

+ COMMENTS